Our fisheries are changing – and the climate crisis could be the culprit.

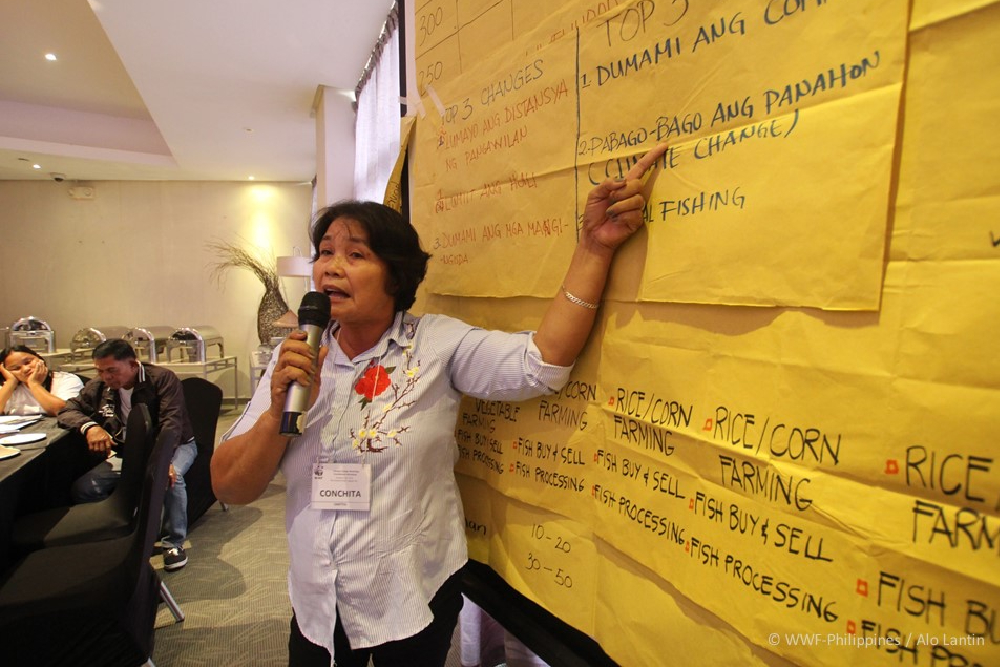

Staff from the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Philippines and consultants from the University of British Columbia (UBC) met with local academics and small-scale fishermen from Lagonoy Gulf and Mindoro Strait on the 9th and 10th of October to discuss the effects of climate change on coastal communities.

As part of the workshop, fishermen were invited to discuss the ways in which their livelihoods had changed over the years, as well as what they suspected were the sources of these changes. Their stories painted a grim picture for the future of Philippine fisheries.

“We catch less small pelagic fish these days. Where before we could catch around 100 kilograms a trip, nowadays we catch less than 50, if anything at all,” explained Bernard Mayo, Chairperson of the MFARMC of Mamburao, Mindoro. Overfishing and behavioral changes brought on by a fluctuating climate have caused fish catches to dwindle, while erratic weather has cut down the number of days in a year that are open to fishing.

“The storms are stronger and the temperatures are hotter nowadays, especially from March to May. You can feel it in the water. It’s not as easy to fish these days as it used to be,” adds Mayo, shaking his head.

Across the country, tuna fishermen in Lagonoy Gulf are finding themselves struggling to bring home a catch. Joel Bongkingki, a fisherman from Bicol, recalls the lengths that many have been forced to go in order to land fish for the marketplace.

“You used to be able to catch fish right here in the Gulf, along the shore. Took no longer than minutes. Didn’t even need to head out in a boat. Now the fish have escaped far out to sea, where its colder,” narrates Bongkingki. As ocean temperatures have risen, commercial fish have sought out colder, more comfortable habitats in the pelagic deep of international waters. For small-scale municipal fishermen used to the coast, such changes are a danger to livelihoods.

“A ten-minute fishing trip became a day long. Then two days. Then three. Today, some spend as much as five days out at sea. Some don’t come home anymore – not even their boats,” narrates Bongkingki. Smaller and smaller catches and ever more desperate times have forced fishermen to push the boundaries of what is safe, in order to provide sustenance for their families.

Our dependence on fishing could plunge us into disaster should the climate crisis cause fisheries to collapse.

“We’re especially vulnerable in the Philippines because we rely heavily on fisheries. If something happens to our fisheries, it’d be a disaster for us,” says Professor Ronnel Dioneda of Bicol University. The Philippines sits at the center of the coral triangle, reminds Dioneda, and 70% of the countries’ protein intake comes from fisheries. The country is also the eighth biggest supplier of fish in the world, providing 3.5% of the world’s fish. The Philippines relies heavily on fishery resources both for sustenance and for economic prosperity, and their loss would spell disaster for the country.

“The effects of climate change start with, of course, the climate. The weather changes, and storms get stronger. Then the fish stocks feel it, then those who live off them, and before you know it, the whole fishery has changed,” details Dioneda.

While reports of changing fisheries have been recorded across the country, a lack of research and empirical data has kept scientists and policy makers hesitant in listing climate change as a threat to marine resources. The stories shared by the fishermen of Bicol and Mindoro suggest it might be worth looking into the relationship between climate change and fisheries, however.

“It’s hard to say for certain what’s causing what. We don’t have the data sets yet. We can take all this evidence as a signal, though, that climate change is having some sort of effect on our fisheries,” says Professor Jimmy Masagca, Associate Professor at Catanduanes State University. Growing concern over a future defined by hunger and food insecurity is pushing scientists to explore all possible dangers to agriculture and fishing, and climate change research has taken center stage in discussions on conservation.

“Either way, we shouldn’t be afraid of climate change. We just need to learn to adapt to it,” adds Masagca.

“I’m not afraid of climate change. There’s still a lot we can do about it. What I’m worried about is that no one’s going to do anything to get ready for what is to come,” says Jomar Abibuag, a small-scale fisherman from Camarines Sur. In the face of current threats, WWF-Philippines works with its partner fisheries in the pursuit of diversified livelihoods and profitable fishery businesses. The climate crisis remains a threat, but the fishermen of the Philippines are preparing to face it.

“We’ve seen changes in our fisheries, but nothing major so far. In the future, however… Well, as much as possible, we’d like our fish to stay,” adds Abibuag with a confident nod of his head. Despite the overwhelming challenge presented by climate changes, many fishermen continue to hope for a fruitful tomorrow. Support WWF-Philippines, and help us ready our fishermen for the current climate crisis.